Lessico

Ateneo di Naucrati

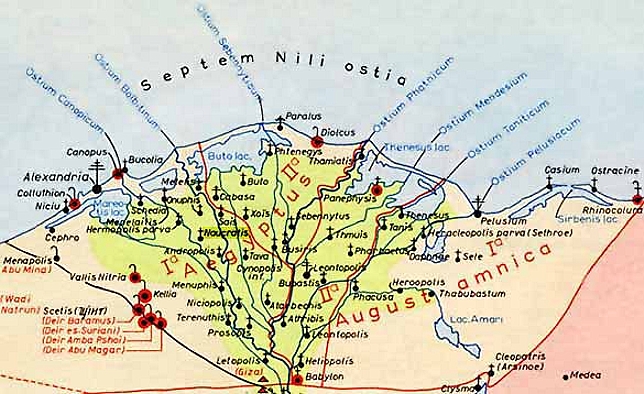

Erudito greco del II-III secolo dC. Di lui sappiamo solo quanto ci dice egli stesso incidentalmente nella sua opera: nacque a Naucrati in Egitto nel delta del Nilo vicino al ramo canopico del Nilo (localizzata a Kom-el-Gaif/Kom Gi eif/Kom Gaef, appena a sudest di Damanhur), e fu a Roma ai tempi dell'imperatore Commodo, al quale sopravvisse però di parecchi anni. Commodo (161-192) fu imperatore a partire dal 180 fino alla morte, quando fu ucciso da un gladiatore in un'ennesima congiura tramata dalla concubina Marcia.

Ateneo è autore di un'opera che ci è pervenuta, Deipnosophistaí (Sapienti a banchetto): durante un convito offerto da un ricco pontefice romano nelle feste Parilie, numerosi dotti greci (letterati, filosofi, medici, giuristi) prendono occasione dalle vivande per dissertare sui più svariati argomenti. L'opera, di pura compilazione, s'inserisce nella tradizione erudita di età alessandrina e tarda; prolissa e praticamente illeggibile, ha peraltro un valore inestimabile per la lessicografia, oltre che per le notizie e i frammenti che ha conservato di autori e di opere perdute, soprattutto della commedia greca.

All'interno del XV libro è presente una raccolta di 25 scoli attici risalente a fine VI-V secolo aC. Si tratta di una collazione di brevi poesie legate all'uso di recitare o improvvisare versi a simposio; alcune di esse furono quindi composte per improvvisazione durante un banchetto (e successivamente trascritte nella raccolta), altre sarebbero state composte, invece, al fine di essere in seguito recitate a convito. In ogni caso si sentono forti i tratti della recitazione orale e dell'improvvisazione, al pari di come si può osservare (all'interno di tutta la lirica greca) solo nella raccolta di elegie di Teognide, poeta elegiaco greco del VI secolo aC.

Naucrati

- Antica città dell’Egitto di fondazione greca, fondata secondo Strabone![]() dai Milesi di Mileto

dai Milesi di Mileto![]() nel sec. VII aC, oppure, secondo Erodoto

nel sec. VII aC, oppure, secondo Erodoto![]() ,

frutto di una fondazione collettiva (intorno al 570 aC) alla quale

parteciparono Chio, Teos, Focea, Clazomene, Rodi, Cnido, Alicarnasso, Mileto,

Samo, Mitilene, Faselis, con il consenso del faraone Amasi.

,

frutto di una fondazione collettiva (intorno al 570 aC) alla quale

parteciparono Chio, Teos, Focea, Clazomene, Rodi, Cnido, Alicarnasso, Mileto,

Samo, Mitilene, Faselis, con il consenso del faraone Amasi.

Naucrati è situata nella regione del delta del Nilo vicino al ramo canopico del Nilo che ha preso il nome dalla città di Canopo, oggi Abukir. L’importanza di questo centro risiede nella sua condizione di “emporio”, cioè di vero e proprio “centro d’affari” per i mercanti greci in Egitto, alcuni dei quali vi si stabilirono in maniera definitiva. La città non era considerata dunque una colonia vera e propria, e cioè una nuova polis, ma piuttosto un punto di riferimento ellenico in terra egiziana. Particolarmente fiorente in età saitica – durante la quale i faraoni promossero frequenti contatti con il mondo greco – Naucrati rimase centro di grande importanza anche nei secoli successivi, in età tolemaica e sotto la dominazione romana.

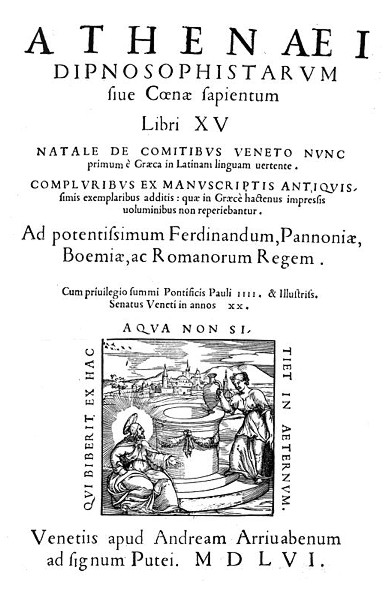

La prima

traduzione latina di Ateneo fu opera di Natale Conti![]() (Natalis

Comes; Hieronymus Comes; Natalis de Comitibus; Natalis Comitum Venetus;

Natalis Comitum), umanista e storiografo, nato probabilmente a Milano nel 1520

e morto nel 1582. Le sue origini erano verosimilmente romane o venete. Questa

traduzione vide la luce a Venezia nel 1556 con il titolo Athenaei

Dipnosophistarum sive Coenae sapientum libri XV. Natale de Comitibus Veneto

nunc primum e Graeca in Latinam linguam vertente. Compluribus ex manuscriptis antiquissimis

exemplaribus additis: quae in Graece hactenus impressis voluminibus non

reperiebantur. Venetiis: apud Andream Arrivabenum ad signum Putei,

1556. L'editore fu appunto Andrea Arrivabene (Venezia 1534-1570), tipografo,

figlio di Giorgio e fratello di Francesco Antonio, di origine mantovana, che

aveva bottega in Marzaria e che aveva come emblema un pozzo. Fu sospettato di

luteranesimo dall'Inquisizione. Tutto il suo magazzino librario, l'insegna e

l'azienda passarono a Francesco Ziletti.

(Natalis

Comes; Hieronymus Comes; Natalis de Comitibus; Natalis Comitum Venetus;

Natalis Comitum), umanista e storiografo, nato probabilmente a Milano nel 1520

e morto nel 1582. Le sue origini erano verosimilmente romane o venete. Questa

traduzione vide la luce a Venezia nel 1556 con il titolo Athenaei

Dipnosophistarum sive Coenae sapientum libri XV. Natale de Comitibus Veneto

nunc primum e Graeca in Latinam linguam vertente. Compluribus ex manuscriptis antiquissimis

exemplaribus additis: quae in Graece hactenus impressis voluminibus non

reperiebantur. Venetiis: apud Andream Arrivabenum ad signum Putei,

1556. L'editore fu appunto Andrea Arrivabene (Venezia 1534-1570), tipografo,

figlio di Giorgio e fratello di Francesco Antonio, di origine mantovana, che

aveva bottega in Marzaria e che aveva come emblema un pozzo. Fu sospettato di

luteranesimo dall'Inquisizione. Tutto il suo magazzino librario, l'insegna e

l'azienda passarono a Francesco Ziletti.

Elenco

dei sapienti presenti al banchetto

organizzato da Publio Livio Larense

oltre a Timocrate amico e interlocutore di Ateneo

Mauro

Emiliano, grammatico

Alcide di Alessandria, musico

Amebeo, suonatore d'arpa e cantante

Arriano, grammatico

Teodoro il Cinico, detto Cynulcus, filosofo

Dafno di Efeso, medico

Democrito di Nicomedia, filosofo

Dionisocle, medico

Claudio Galeno![]() , medico

, medico

Publio Livio Larense, pontefice minore romano

Leonida dell'Elide, grammatico

Magnus, forse un Romano

Masurio, giurista, poeta di giambi e musico

Mirtilo di Tessaglia, grammatico

Palamede di Elea, collezionista di parole

Filadelfo Egiziano, filosofo

Plutarco di Alessandria, grammatico

Pontiano di Nicomedia, filosofo

Rufino di Nicea, medico

Ulpiano di Tiro, giurista oppure grammatico

Varo, grammatico

Zoilo, grammatico.

alcuni personaggi sono di dubbia identificazione

Dictionary

of Greek and Roman biography and mythology

William Smith, Boston, 1867

Athenaeus (Ἀθήναιος), a native of Naucratis, a town on the left side of the Canopic mouth of

the Nile, is called by Suidas![]() a γραμματικός, a term which may be best rendered into English, a literary

man. Suidas places him in the "times of Marcus," but

whether by this is meant Marcus Aurelius is uncertain, as Caracalla was also

Marcus Antoninus. We know, however, that Oppian

a γραμματικός, a term which may be best rendered into English, a literary

man. Suidas places him in the "times of Marcus," but

whether by this is meant Marcus Aurelius is uncertain, as Caracalla was also

Marcus Antoninus. We know, however, that Oppian![]() , who wrote a work called Halieutica

inscribed to Caracalla, was a little anterior to him. (Athen. i. p. 13), and

that Commodus was dead when he wrote (xii. p. 537), so that he may have been

born in the reign of Aurelius, but flourished under his successors. Part of

his work must have been written after AD 228, the date given by Dion

Cassius

, who wrote a work called Halieutica

inscribed to Caracalla, was a little anterior to him. (Athen. i. p. 13), and

that Commodus was dead when he wrote (xii. p. 537), so that he may have been

born in the reign of Aurelius, but flourished under his successors. Part of

his work must have been written after AD 228, the date given by Dion

Cassius![]() for the death of Ulpian the lawyer, which event he

mentions, (xv. p. 686.)

for the death of Ulpian the lawyer, which event he

mentions, (xv. p. 686.)

His extant work is entitled the Deipnosophistae, i. e. the Banquet of the Learned, or else, perhaps, as has lately been suggested, The Contrivers of Feasts. It may be considered one of the earliest collections of what are called Ana, being an immense mass of anecdotes, extracts from the writings of poets, historians, dramatists, philosophers, orators, and physicians, of facts in natural history, criticisms, and discussions on almost every conceivable subject, especially on Gastronomy, upon which noble science he mentions a work (now lost) of Archestratus, whose place his own 15 books have probably supplied. It is in short a collection of stories from the memory and common-place book of a Greek gentleman of the third century of the Christian era, of enormous reading, extreme love of good eating, and respectable ability. Some notion of the materials which he had amassed for the work, may be formed from the fact, which he tells us himself, that he had read and made extracts from 800 plays of the middle comedy only. (viii. p. 336.)

Athenaeus represents himself as describing to his

friend Timocrates, a banquet given at the house of Laurentius (Λαρήνσιος), a noble Roman, to several guests, of whom the

best known are Galen![]() , a physician, and Ulpian, the lawyer. The work is

in the form of a dialogue, in which these guests are the interlocutors,

related to Timocrates: a double machinery, which would have been inconvenient

to an author who had a real talent for dramatic writing, but which in the

hands of Athenaeus, who had none, is wholly unmanageable. As a work of art the

failure is complete. Unity of time and dramatic probability are utterly

violated by the supposition that so immense a work is the record of the

conversation at a single banquet, and "by

the absurdity of collecting at it the produce of every season of the year.

Long quotations and intricate discussions introduced apropos of some trifling

incident, entirely destroy the form of the dialogue, so that before we have

finished a speech we forget who was the speaker. And when in addition to this

confusion we are suddenly brought back to the tiresome Timocrates, we are

quite provoked at the clumsy way in which the book is put together. But as a

work illustrative of ancient manners, as a collection of curious facts, names

of authors and fragments, which, but for Athenaeus, would utterly have

perished; in short, as a body of amusing antiquarian research, it

would be difficult to praise the Deipnosophistae too highly.

, a physician, and Ulpian, the lawyer. The work is

in the form of a dialogue, in which these guests are the interlocutors,

related to Timocrates: a double machinery, which would have been inconvenient

to an author who had a real talent for dramatic writing, but which in the

hands of Athenaeus, who had none, is wholly unmanageable. As a work of art the

failure is complete. Unity of time and dramatic probability are utterly

violated by the supposition that so immense a work is the record of the

conversation at a single banquet, and "by

the absurdity of collecting at it the produce of every season of the year.

Long quotations and intricate discussions introduced apropos of some trifling

incident, entirely destroy the form of the dialogue, so that before we have

finished a speech we forget who was the speaker. And when in addition to this

confusion we are suddenly brought back to the tiresome Timocrates, we are

quite provoked at the clumsy way in which the book is put together. But as a

work illustrative of ancient manners, as a collection of curious facts, names

of authors and fragments, which, but for Athenaeus, would utterly have

perished; in short, as a body of amusing antiquarian research, it

would be difficult to praise the Deipnosophistae too highly.

The work begins, somewhat absurdly, considering the

difference between a discussion on the Immortality of the Soul, and one on the

Pleasures of the Stomach, with an exact imitation of the opening of Plato's

Phaedo![]() , — Athenaeus and Timocrates being substituted for

Phaedo and Echecrates. The praises of Laurentius are then introduced, and the

conversation of the savans begins. It would be impossible to give an account

of the contents of the book; a few specimens therefore must suffice. "We

have anecdotes of gourmands, as of Apicius

, — Athenaeus and Timocrates being substituted for

Phaedo and Echecrates. The praises of Laurentius are then introduced, and the

conversation of the savans begins. It would be impossible to give an account

of the contents of the book; a few specimens therefore must suffice. "We

have anecdotes of gourmands, as of Apicius![]() (the second of the three illustrious gluttons of

that name), who is said to have spent many thousands on his stomach, and to

have lived at Minturnae in the reign of Tiberius

(the second of the three illustrious gluttons of

that name), who is said to have spent many thousands on his stomach, and to

have lived at Minturnae in the reign of Tiberius![]() , whence he sailed to Africa, in search of good

lobsters; but finding, as he approached the shore, that they were no larger

than those which he ate in Italy, he turned back without landing. Sometimes we

have anecdotes to prove assertions in natural history, e. g. it is shown that

water is nutritious, by the statement that it nourishes the τέττιξ, and because fluids generally are so, as milk and

honey, by the latter of which Democritus of Abdera

, whence he sailed to Africa, in search of good

lobsters; but finding, as he approached the shore, that they were no larger

than those which he ate in Italy, he turned back without landing. Sometimes we

have anecdotes to prove assertions in natural history, e. g. it is shown that

water is nutritious, by the statement that it nourishes the τέττιξ, and because fluids generally are so, as milk and

honey, by the latter of which Democritus of Abdera![]() allowed himself to be kept alive over the

Thesmophoria (though he had determined to starve himself), in order that the

mourning for his death might not prevent his maidservants from celebrating

the festival. The story of the Pinna and Pinnoteer (πιννοφύλαξ or πιννοτήρης) is told in the course of the disquisitions on

shell-fish. The pinna is a bivalve shell-fish (ὄστρεον), the pinnoteer a small crab, who inhabits the

pinna's shell. As soon as the small fish on which the pinna subsists have swum

in, the pinnoteer bites the pinna as a signal to him to close his shell and

secure them. Grammatical discussions are mixed up with gastronomic; e. g. the

account of the ἀμυγδάλη begins with the laws of its accentuation; of eggs, by an inquiry into

the spelling of the word, whether ὠόν, ὤϊον,

ὤεον or ὠάριον. Quotations are made in support of each, and we are

told that ὠά was formerly

the same as ὑπερῷα, from which fact he deduces an explanation of the story of Helen's

allowed himself to be kept alive over the

Thesmophoria (though he had determined to starve himself), in order that the

mourning for his death might not prevent his maidservants from celebrating

the festival. The story of the Pinna and Pinnoteer (πιννοφύλαξ or πιννοτήρης) is told in the course of the disquisitions on

shell-fish. The pinna is a bivalve shell-fish (ὄστρεον), the pinnoteer a small crab, who inhabits the

pinna's shell. As soon as the small fish on which the pinna subsists have swum

in, the pinnoteer bites the pinna as a signal to him to close his shell and

secure them. Grammatical discussions are mixed up with gastronomic; e. g. the

account of the ἀμυγδάλη begins with the laws of its accentuation; of eggs, by an inquiry into

the spelling of the word, whether ὠόν, ὤϊον,

ὤεον or ὠάριον. Quotations are made in support of each, and we are

told that ὠά was formerly

the same as ὑπερῷα, from which fact he deduces an explanation of the story of Helen's![]() birth from an egg. This suggests to him a quotation from Eriphus, who says

that Leda

birth from an egg. This suggests to him a quotation from Eriphus, who says

that Leda![]() produced goose's eggs; and so he wanders on through every variety of subject

connected with eggs. This will give some notion of the discursive manner in

which he extracts all kinds of facts from the vast stores of his erudition.

Sometimes he connects different pieces of knowledge by a mere similarity of

sounds. Cynulcus, one of the guests, calls for bread (ἄρτος), "not however for Artus king of the

Messapians;" and then we are led back from Artus the king to Artus the

eatable, and from that to salted meats, which brings in a grammatical

discussion on the word τάριχος, whether it is masculine in Attic or not. Sometimes antiquarian points

are discussed, especially Homeric. Thus, he examines the times of day at which

the Homeric meals took place, and the genuineness of some of the lines in the

Iliad and Odyssey, as

produced goose's eggs; and so he wanders on through every variety of subject

connected with eggs. This will give some notion of the discursive manner in

which he extracts all kinds of facts from the vast stores of his erudition.

Sometimes he connects different pieces of knowledge by a mere similarity of

sounds. Cynulcus, one of the guests, calls for bread (ἄρτος), "not however for Artus king of the

Messapians;" and then we are led back from Artus the king to Artus the

eatable, and from that to salted meats, which brings in a grammatical

discussion on the word τάριχος, whether it is masculine in Attic or not. Sometimes antiquarian points

are discussed, especially Homeric. Thus, he examines the times of day at which

the Homeric meals took place, and the genuineness of some of the lines in the

Iliad and Odyssey, as

ᾔδεε γὰρ κατὰ θυμν ἀδελφέον, ὡς ἐπονεῖτο,

which he pronounces spurious, and only introduced to explain

αὐτόματος δὲ οἱ ἦλθε βοὴν ἀγαθὸς Μὲνέλαος.

His etymological conjectures

are in the usual style of ancient philology. In proving the religious duty of

drunkenness, as he considers it, he derives θοίνη from θεῶν

ἕνεκα

οἰνοῦσθαι and μεθύειν from μετὰ τὸ

θύειν. We often obtain from him curious pieces of information on subjects

connected with ancient art, as that the kind of drinking-cup called ῥυτόν was first devised by Ptolemy Philadelphus as an

ornament for the statues of his queen, Arsinoë. At the end of the work is a

collection of scolia and other songs, which the savans recite. One of these is

a real curiosity, — a song by Aristotle![]() in praise of ἀρετή.

in praise of ἀρετή.

Among the authors, whose works are now lost, from

whom Athenaeus gives extracts, are Alcaeus![]() , Agathon the tragic poet, Antisthenes the

philosopher, Archilochus the inventor of iambics, Menander

, Agathon the tragic poet, Antisthenes the

philosopher, Archilochus the inventor of iambics, Menander![]() and his contemporary Diphilus, Epimenides of Crete,

Empedocles

and his contemporary Diphilus, Epimenides of Crete,

Empedocles![]() of Agrigentum, Cratinus

of Agrigentum, Cratinus![]() , Eupolis (Hor. Sat. i. 4.1), Alcman,

Epicurus (whom he represents as a wasteful glutton), and many others whose

names are well known. In all, he cites nearly. 800 authors and more than 1200

separate works. Athenaeus was also the author of a lost book περὶ

τῶν ἐν Συρίᾳ

βασιλευςάντων, which

probably, from the specimen of it in the Deipnosophists, and the obvious

unfitness of Athenaeus to be a historian, was rather a collection of anecdotes

than a connected history.

, Eupolis (Hor. Sat. i. 4.1), Alcman,

Epicurus (whom he represents as a wasteful glutton), and many others whose

names are well known. In all, he cites nearly. 800 authors and more than 1200

separate works. Athenaeus was also the author of a lost book περὶ

τῶν ἐν Συρίᾳ

βασιλευςάντων, which

probably, from the specimen of it in the Deipnosophists, and the obvious

unfitness of Athenaeus to be a historian, was rather a collection of anecdotes

than a connected history.

Of the Deipnosophists

the first two books, and parts of the third, eleventh, and fifteenth, exist

only in an Epitome, whose date and author are unknown. The original work,

however, was rare in the time of Eustathius![]() (latter

part of 12th cent.); for Bentley has shown, by examining nearly a hundred of

his references to Athenaeus, that his only knowledge of him was through the

Epitome. (Phalaris, p. 130, &c.) Perizonius (preface to Aelian

(latter

part of 12th cent.); for Bentley has shown, by examining nearly a hundred of

his references to Athenaeus, that his only knowledge of him was through the

Epitome. (Phalaris, p. 130, &c.) Perizonius (preface to Aelian![]() quoted by

Schweighäuser) has proved that Aelian transferred large

portions of the work to his Various Histories (middle of 3rd cent.), a

robbery which must have been committed almost in the life-time of the pillaged

author. The Deipnosophists also furnished to Macrobius

quoted by

Schweighäuser) has proved that Aelian transferred large

portions of the work to his Various Histories (middle of 3rd cent.), a

robbery which must have been committed almost in the life-time of the pillaged

author. The Deipnosophists also furnished to Macrobius![]() the idea and much of the matter of his Saturnalia

(end of 4th cent.); but no one has availed himself so largely of Athenaeus's

erudition as Eustathius.

the idea and much of the matter of his Saturnalia

(end of 4th cent.); but no one has availed himself so largely of Athenaeus's

erudition as Eustathius.

Only one original MS. of Athenaeus now exists, called by Schweighäuser the Codex Verieto-Parisiensis. From this all the others which we now possess are copies; so that the text of the work, especially in the poetical parts, is in a very unsettled state. The MS. was brought from Greece by cardinal Bessarion, and after his death was placed in the library of St. Mark at Venice, whence it was taken to Paris by order of Napoleon, and there for the first time collated by Schweighäuser's son. It is probably of the date of the 10th century. The subscript is always placed after, instead of under, the vowel with which it is connected, and the whole is written without contractions.

The first edition of Athenaeus was that of Aldus, Venice, 1514; a second published at Basle, 1535; a third by Casaubon at Geneva, 1597, with the Latin version of Dalecampius (Jacques Dalechamp of Caen), and a commentary published in 1600; a fourth by Schweighäuser, Strasburg, 14 vols. 8vo. 1801-1807, founded on a collation of the abovementioned MS. and also of a valuable copy of the Epitome; a fifth by W. Dindorf, 3 vols. 8vo., Leipsic, 1827. The last is the best, Schweighäuser not having availed himself sufficiently of the sagacity of previous critics in amending the text, and being himself apparently very ignorant of metrical laws. There is a translation of Athenaeus into French by M. Lefevre de Villebrune, under the title "Banquet des Savans, par Athenée," 1789-1791, 5 vols. 4to. A good article on Schweighäuser's edition will be found in the Edinburgh Review, vol. iii. 1803. [G. E. L. C.]

Athenaeus

Athenaeus

(Latin Athenaeus Naucratita), of Naucratis in Egypt, Greek rhetorician and

grammarian, flourished about the end of the 2nd and beginning of the 3rd

century A.D. Suidas![]() only

tells us that he lived in the times of Marcus; but the contempt with which he

speaks of Commodus (died 192) shows that he survived that emperor.

only

tells us that he lived in the times of Marcus; but the contempt with which he

speaks of Commodus (died 192) shows that he survived that emperor.

Athenaeus himself states that he was the author of a treatise on the thratta -- a kind of fish mentioned by Archippus and other comic poets -- and of a history of the Syrian kings, both of which works are lost.

We

still possess the Deipnosophistae, which may mean dinner-table

philosophers or authorities on banquets, in fifteen books. The first two books,

and parts of the third, eleventh and fifteenth, are only extant in epitome,

but otherwise we seem to possess the work entire. It is an immense store-house

of miscellaneous information, chiefly on matters connected with the table, but

also containing remarks on music, songs, dances, games, courtesans. It is full

of quotations from writers whose works have not come down to us; nearly 800

writers and 2500 separate writings are referred to by Athenaeus; and he boasts

of having read 800 plays of the Middle Comedy![]() alone.

The plan of the Deipnosophistae is exceedingly cumbersome, and is badly

carried out. It professes to be an account given by the author to his friend

Timocrates of a banquet held at the house of Laurentius (or Larentius), a

scholar and wealth patron of art. It is thus a dialogue within a dialogue,

after the manner of Plato

alone.

The plan of the Deipnosophistae is exceedingly cumbersome, and is badly

carried out. It professes to be an account given by the author to his friend

Timocrates of a banquet held at the house of Laurentius (or Larentius), a

scholar and wealth patron of art. It is thus a dialogue within a dialogue,

after the manner of Plato![]() , but a

conversation of sufficient length to occupy several days (though represented

as taking place in one) could not be conveyed in a style similar to the short

conversations of Socrates

, but a

conversation of sufficient length to occupy several days (though represented

as taking place in one) could not be conveyed in a style similar to the short

conversations of Socrates![]() . Among

the twenty-nine guests are Galen

. Among

the twenty-nine guests are Galen![]() and

Ulpian, but they are all probably fictitious personages, and the majority take

no part in the conversation. If Ulpian is identical with the famous jurist,

the Deipnosophistae may have been written after his death in 228; but

the jurist was murdered by the Praetorian guards, whereas Ulpian in Athenaeus

dies a natural death. The conversation ranges from the dishes put before the

guests to literary manners of every description, including points of grammar

and criticism; and the guests are expected to bring with them extracts from

the poets, which are read aloud and discussed at table. The whole is but a

clumsy apparatus for displaying the varied and extensive reading of the author.

As a work of art it can take but a low rank, but as a repertory of fragments

and morsels of information it is invaluable.

and

Ulpian, but they are all probably fictitious personages, and the majority take

no part in the conversation. If Ulpian is identical with the famous jurist,

the Deipnosophistae may have been written after his death in 228; but

the jurist was murdered by the Praetorian guards, whereas Ulpian in Athenaeus

dies a natural death. The conversation ranges from the dishes put before the

guests to literary manners of every description, including points of grammar

and criticism; and the guests are expected to bring with them extracts from

the poets, which are read aloud and discussed at table. The whole is but a

clumsy apparatus for displaying the varied and extensive reading of the author.

As a work of art it can take but a low rank, but as a repertory of fragments

and morsels of information it is invaluable.

Without the works of Athenaeus much valuable information about the ancient world would be missing, and many ancient Greek authors (including Archestratus) would be entirely unknown. Book XIII is an important source for studies of sexuality in classical and Hellenistic Greece.

The most valuable recent publication about Athenaeus and The Deipnosophists is Athenaeus and his world edited by David Braund and John Wilkins, (2000). The book is a collection of 41 essays by literary specialists and historians upon various aspects of the work.

Les seuls éléments que nous connaissons sur Athénée proviennent de son œuvre. Né en Égypte, probablement sous Marc-Aurèle, il aurait fait ses études à Alexandrie où il aurait vécu de 170 à 230. Il se serait ensuite établi à Rome, où il rédige son ouvrage, Deipnosophistaí, « le banquet des sophistes », allusion aux Propos de table de Plutarque et au Banquet de Platon. Selon ce texte lui-même, Athénée aurait également été l'auteur d'un traité sur les monarques de Syrie ainsi que d'un commentaire de la comédie Les Poissons (aujourd'hui disparue) d'un certain Archippos, contemporain d'Aristophane.

Il meurt probablement après 223: les Deipnosophistes évoquent la mort d'un certain Ulpien, qui est peut-être le célèbre juriste Ulpien, mort à cette date. Cependant, cela n'est pas sûr: Athénée décrit la mort d'Ulpien comme « heureuse », au sens où elle ne survient pas au terme d'une longue maladie (686c); or l'Ulpien historique meurt assassiné. Indice plus sûr, les Deipnosophistes sont utilisés au V siècle par le lexicographe Hésychios d'Alexandrie. Enfin, le narrateur de l'œuvre, identifié comme « Athénée », situe son propre récit sous le règne de l'empereur Commode (537f), c'est-à-dire de 181 à 192.

Les Deipnosophistes

Les

Deipnosophistes sont une série de conversations tenues lors d'un dîner

fictif que l'ouvrage place à Rome, au début du III siècle: avant la mort

d'un personnage décrit comme « Galien » (soit en 199 pour le Galien

historique) et après la mort d'« Ulpien ». Il comprend quinze livres au

cours desquels « Athénée », le narrateur, raconte à un interlocuteur nommé

Timocrate les conversations du fameux dîner. Timocrate lui-même ne s'exprime

qu'à une seule reprise, au début du livre I, mais « Athénée » s'adresse

à lui au début et à la fin de la plupart des quinze livres.

Le livre est essentiellement une collection d'anecdotes et de citations, sous

le prétexte d'un banquet donné par le riche Publius Livius Larensis, où les

nombreux convives, fin lettrés, discutent de sujets variés. Ces convives

sont aussi bien des auteurs contemporains que d'illustres morts: ainsi Platon,

dans son Tééthète, avait ressuscité Protagoras pour les besoins de l'œuvre.

Sont nommés Galien, Ulpien, Masurius Sabinus (l'un des auteurs du Digeste),

Zoïle (critique d'Homère), Plutarque, etc. Les auteurs ainsi cités sont

parfois à demi-déguisés par Athénée, par précaution: ainsi, Zoïle ne se

préoccupe jamais dans l'œuvre de questions homériques, pourtant son seul

titre de gloire; Plutarque est présenté comme un simple grammairien; Démocrite

n'est pas mentionné comme natif d'Abdère, mais de Nicomédie. Réunis autour

d'une même table, ces auteurs discutent à coup de citations d'auteurs

anciens sur un très grand nombre de sujets:

livre I: la

littérature gastronomique, le vin et la nourriture dans l'œuvre d'Homère,

le vin;

livres II et III: les hors d'œuvres et le pain;

livres IV: l'organisation des repas et la musique;

livre V: luxe et ostentation;

livre VI: parasites et flatterie;

livres VII et VIII: le poisson;

livre IX: la viande et la volaille;

livre X: la gloutonnerie, le vin;

livre XI: les coupes;

livre XII: les conventions sociales;

livre XIII: l'amour;

livre XIV: la musique, les desserts;

livre XV: couronnes et parfums.

La compilation d'Athénée est précieuse, car on estime à 1500 le nombre d'ouvrages cités, dont la grande majorité sont aujourd'hui perdus, pour environ 700 auteurs représentés. La plupart des citations sont attribuées à un auteur et référencées. Les citations longues ont probablement été relevées par Athénée directement, au cours de ses lectures: on ne connaît aucune compilation de citations de ce type. En revanche, les citations plus courtes, plus particulièrement celles qui touchent à la lexicographie et à la grammaire, sont probablement issues de sources de seconde main.

Les Deipnosophistes est un outil précieux sur la littérature et la vie en Grèce dans l'Antiquité. Il est également une bonne source sur les banquets grecs (symposiums), les plats qui y étaient servis, et les spectacles qui y étaient proposés. C'est donc aussi un véritable traité de gastronomie, avec des informations sur les coutumes de table, les aliments, les menus, la vaisselle, le vin. Les digressions auxquelles se livrent les convives font passer sous nos yeux toute la société antique.

La tradition manuscrite

L'œuvre d'Athénée nous est parvenue par l'intermédiaire d'un manuscrit byzantin, copié par Jean le Calligraphe à Constantinople au X siècle, apporté en Italie par Jean Aurispa au XV siècle et acheté par le cardinal Bessarion. Conservé à la Bibliothèque Saint-Marc de Venise, il est connu sous le nom de Marcianus Venetus 447 ou de Marcianus A. À ce codex composé de 370 folios manquent les deux premiers livres, le début du troisième, une partie du livre XV et quelques passages dispersés.

Ces carences sont palliées par un résumé byzantin tardif que la tradition nomme l'Épitomé. Il se concentre sur les citations contenues dans l'ouvrage, en laissant de côté la partie conversationnelle et en omettant souvent les références. Malgré tout, les philologues s'accordent à le reconnaître plus fidèle à l'original que le Marcianus A. Il est difficile à dater: le seul indice positif est qu'Eustathe de Thessalonique l'emploie largement quand il enseigne à l'école patriarcale de Constantinople, soit avant 1175. Enfin, le texte est complété par le Lexique d'Hésychios ou encore la Souda, encyclopédie byzantine de la fin du XI siècle: ils ont préservé des versions différentes de la tradition manuscrite directe, et parfois préférables.

Enfin, il faut noter que le Marcianus A comporte une série de notes témoignant de Deipnosophistes en trente livres, au lieu des quinze connus actuellement, ce qui explique certaines incohérences dans le texte, et notamment dans la présentation des convives. Ce découpage est confirmé par des exemplaires du Lexique d'Hésychios qui attestent de la connaissance de l'œuvre en trente livres.

Éditions postérieures

L'édition princeps d'Athénée date d'août 1514. Elle est due à Alde Manuce et se fonde sur un manuscrit établi par le Crétois Marco Musuro. Elle ne se rattache qu'indirectement au Venetus A, alors inaccessible. Vite épuisée, l'Aldine est suivie deux ans plus tard par l'édition de Christian Herlin, imprimée par Jean Walder de Bâle. En 1556, Andrea Arrivabene imprime à Venise la première traduction en latin d'Athénée, œuvre de Natalis Comes sur la base de l'Aldine. De médiocre qualité, elle est surpassée en 1583 par la traduction du médecin Jacques Daléchamp, fondée sur l'édition de Bâle. C'est cette dernière que choisit l'humaniste protestant Isaac Casaubon pour la mettre en regard de son édition des Deipnosophistes, publiée en 1597. Celle-ci marque une étape importante dans l'histoire de la transmission des œuvres grecques et latines. La pagination de Casaubon reste ainsi utilisée de manière courante depuis le XIX siècle.

La première traduction d'Athénée en français est due à l'abbé Michel de Marolles, en 1680. De niveau médiocre, elle est suivie en 1789-1791 par celle de Jean Baptiste Lefebvre de Villebrune, qui se distingue par son acrimonie contre Casaubon. Au XIX siècle, le strasbourgeois Jean Schweighæuser, les allemands Wilhelm Dindorf et Auguste Meineke marquent, par leurs éditions, l'histoire du texte d'Athénée. C'est enfin Georg Kaibel qui livre, en 1887-1890, l'édition considérée aujourd'hui comme celle de référence.

Natale

Conti

Natalis Comes

Natalis Comes (nom latinisé), ou encore Natale Conti, Noël Conti (Milan, v. 1520 - 1582). Il est né à Milan et mort dans la même cité en 1582. Il a cependant passé toute sa vie à Venise et y a publié tous ses livres.

Natale Conti était un grand spécialiste de la mythologie grecque et égyptienne. Il croyait que dans les fables mythologiques étaient renfermées les vérités des sciences et la philosophie, et que les sages avaient choisi cette forme pour faciliter sa diffusion.

Au XIX siècle, Conti a été considéré comme le précurseur du symbolisme dans le domaine de l'histoire des religions (Carl Gustav Jung, Mircea Eliade, Ernst Cassirer). Il a laissé plusieurs recueils de poèmes néo-latins et des traductions.

Il est auteur:

de plusieurs poèmes latins, De Horis, de Anno, de Venatione, etc.;

d'une Histoire de mon temps, 1572 (latin);

d'un ouvrage important intitulé Mythologie, Venise, 1551 et 1581, où il explique par la philosophie les mythes des anciens. La première édition fut donnée par les Alde en 1551; cet ouvrage est le plus célèbre et il a servi comme référence pour la plupart d'artistes et poètes de la Renaissance dans toute l'Europe; l'édition de 1596 contient aussi De Venatione, un texte consacré à la chasse, et la Mythologie des muses du naturaliste français Geoffroi Linocier.

Il est le premier traducteur d'Athénée et a traduit plusieurs autres écrivains grecs.

Jules César

Scaliger![]() l'avait

qualifié de "Homo futilissimus".

l'avait

qualifié de "Homo futilissimus".